Yakety Yak |

||

Don't talk back. Perspectives on the rock 'n' roll and R&B of the '50s, '60s and '70s by Freddy Mac

and Snackie Archives |

Friday, December 06, 2002

The Funk Brothers:     I finally got out to see "Standing in the Shadows of Motown" yesterday, and my overwhelming reaction is one of gratitude to the filmmakers. This feature-length documentary on the careers of the "Funk Brothers" -- the stellar house band for Motown Records during its heyday in the 1960s -- is not just a valuable contribution to rock and soul history, but also a very thoughtful and loving tribute. The idea of the movie is simple. Get whoever's still alive among the Motown sidemen back together, and try to get them a little bit of their due, 35 or 40 years late. Interview them in the "snakepit" -- Motown "Studio A." Cruise around Detroit to places where some of it happened. Hire a few actors to play out a few flashback scenes. Then put the Funk Brothers together on stage for a monster session playing some of the big hits with guest artists. And an important, unspoken rule: Not a current note is to be heard from any of the stars who stood in front of these guys on the Motown stage. No live appearance by Smokey, Stevie, Diana, Michael, etc. (although Martha Reeves is interviewed fairly extensively). Moreover, not a word, live or recorded, from Berry Gordy, the much-honored founder of Motown. This movie is most decidedly not about them. For devotees of Motown, it's a riveting and revealing couple of hours. Andre Braugher of "Homicide" fame narrates a great series of sequences in which even die-hard Motown fans are likely to learn quite a few new tidbits. Did you know that the "Funk Brothers" played behind the Capitols on "Cool Jerk"? Or that they developed some of their rhythms and riffs while working part-time backing up an "exotic dancer" in a Detroit dive? The concert itself is great fun, with strong performances by a number of non-Motown stars. Chaka Khan is totally at ease and in command; Bootsy Collins gets everybody going; and MeShell Ndegeocello somehow stays in the groove with the guys while seemingly trying to exorcise some of her own demons onstage with the Motown songs. Gerald Levert and Tom Scott put two heads together and almost cover what Junior Walker did with one. And a young guy named Ben Harper offers such a fine reading of "I Heard it Through the Grapevine" (Marvin Gaye version), and such right-on comments afterward, that he advances his own career at the same time as saluting the Brothers. The outsider interviews are just right, too. For example, some great perspectives are offered by Hollywood music producer Don Was, who to my ears has occasionally gotten as close as anyone else to reproducing the Motown sound (although of course, no one can completely succeed there). Perhaps the best line of the film comes from another modern admirer, the drummer Steve Jordan, who correctly observes that with instrumental tracks this great, you could have had Deputy Dawg singing over them, and they still would have been huge hits. There are also some very revealing and sometimes touching conversations between the younger artists from the concert and the polite, supportive Motown masters. At times, it seems that this project was put together about 15 years too late. For example, a few grainy video clips are all that we hear from Earl Van Dyke, who reigned over the "gorilla piano," and Robert White, who gave us, among other fine moments, the wonderful guitar lick that opens "My Girl." One wonders if "Shadows" might have benefited from having those two alive and participating. Both died in the '90s. (Of course, bass master James Jamerson and drummer Benny Benjamin are long since gone; their deaths are part of the core story.) One thing is for sure: This film was made just in the nick of time. Lead drummer Richard "Pistol" Allen, who for my money steals the show in the concert, passed away before the movie was even printed, and soft-spoken pianist Johnny Griffith left us just as the movie was being released a couple of weeks ago. Without those two, critical mass would surely have been missing. If the movie has a fault, it is being too literal and repetitive with its message: that these guys were phenomenal musicians, without whom the "Sound of Young America" would never have been the great art that it became, and they never got their due. O.k., o.k., give us credit for being smart enough to absorb that after it's mentioned the first five times. Just let 'em talk, and let 'em play. The perfunctory Vietnam references also seem forced. Yes, perhaps our soldiers listened to Motown songs as they were killing Viet Cong, but that's not much of a connection. What about Edwin Starr's "War"? Not even mentioned. Marvin Gaye's "What's Goin' On" gets prominent discussion, and yet the album's message isn't spotlighted. But these are nitpicks. For a serious Motown fan, this is a must-see, and the DVD will be a must-have. (At the risk of sounding like a bad trailer, you'll never listen to your Motown collection the same way again.) For anyone else, enjoyment of the movie will be in direct proportion to his or her appreciation of the Motor City sound. I had a great time, I learned a lot about something I really enjoy, and I look forward to reading the book. Oh, and there is one other significant item to report: For reasons that I cannot fully explain, I still have a wicked crush on Joan Osborne. Tuesday, December 03, 2002

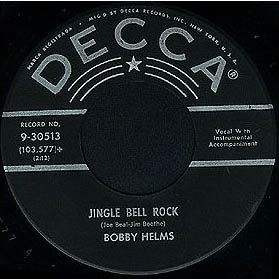

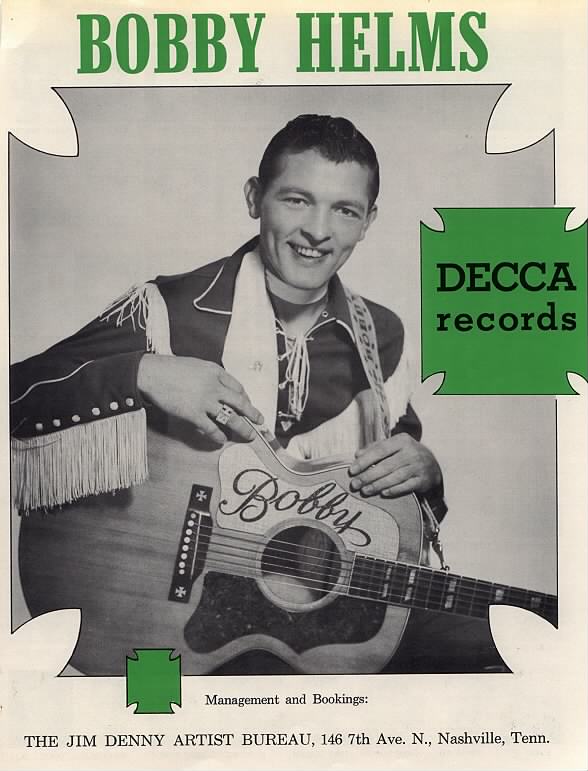

Now the jingle hop has begun: The Thanksgiving weekend agenda at our house includes breaking out the Christmas music once again. The box gets bigger every few years, what with an average of two additions per annum. For the last couple of years, we didn't even get around to playing everything in the box. Lately the acquisitions have included some oddballs. James Brown and Boxcar Willie -- well, they ain't Bing Crosby, if you know what I mean. And when Odetta starts singin' 'bout dat lil baby in a manger, you know this is not your grandpa's Christmas music. (Not my grandpa, anyway.) My spouse and I have been trying to explain the Christmas thing to our two-year-old for the past week or so, and as I drew the first CD out of that box and popped it into the machine, I suggested that we all dance to some Christmas music. When the green light came on and that first cut kicked off, all three of us starting bopping around happily -- merrily, I guess you'd have to say.  And then I realized I was re-enacting a scene from my childhood, when I was three or four years old. Because we were doing the same thing that my parents did with me, and with the very same song: Bobby Helms's "Jingle Bell Rock." And then I realized I was re-enacting a scene from my childhood, when I was three or four years old. Because we were doing the same thing that my parents did with me, and with the very same song: Bobby Helms's "Jingle Bell Rock."

Now don't get me wrong, I know that there are people out there who are sick of this little number. It's corny as hell, and who can avoid being bombarded with it at least once a day for about three weeks every December? But for some reason, I never get tired of it. I just think it's a beautiful way to spend two and a half minutes. There's the awesome hook that starts and ends it -- a little guitar spinoff of a traditional classic that makes a real statement: It's "Jingle Bells," folks, but you never heard it like this before (and in '57, when they made this record, indeed you hadn't). Years later, Joni Mitchell took the same few bars in a much, much darker direction, but with a similar, big impact. The structure of "Jingle Bell Rock" is so simple -- a couple of verses, a couple of bridges, and of course the hokey background chorus gets a crack at a verse, and before you know it, you're putting your partner through one last spin and you're done. And no sappy, drawn-out fade here. A crisp, clean ending with more or less the same hook that started it off. Bravo!  Back in the days when Helms recorded this, it was considered country music. I never paid much attention to that sound back then, or any time since, really. You're talkin' Jim Reeves and Eddy Arnold's style, which is too sticky sweet for me, especially with the saccharine background singers. I think I have an early Willie Nelson record that shows him trying to deal with all that, and it's easy to see that he and Waylon Jennings had to bust out of there or die. (Which suggests an interesting parallel to the difference between the weirdness that passes for "country" music today and the more interesting "American roots" music that is being made by people like Steve Earle, but that's for a different blog entirely.) Back in the days when Helms recorded this, it was considered country music. I never paid much attention to that sound back then, or any time since, really. You're talkin' Jim Reeves and Eddy Arnold's style, which is too sticky sweet for me, especially with the saccharine background singers. I think I have an early Willie Nelson record that shows him trying to deal with all that, and it's easy to see that he and Waylon Jennings had to bust out of there or die. (Which suggests an interesting parallel to the difference between the weirdness that passes for "country" music today and the more interesting "American roots" music that is being made by people like Steve Earle, but that's for a different blog entirely.)

To get back to the point: For a nice little Christmas record to dance to with your loved one, for my money it's hard to beat "Jingle Bell Rock." A bit of research on the song reveals some noteworthy facts. Allegedly its real authors -- Helms and the guitar player with the killer lick, a fellow named Hank "Sugarfoot" Garland -- never got credit for writing it. That credit was given to two guys who wrote a similar song called "Jingle Bell Hop," which Garland and Helms are said to have used as the base for their own composition. These copyright hassles confuse and depress me to no end, but I'm sure what emerged from the studio and wound up on my record player had a lot more to do with Garland and Helms than whatever the other guys wrote. Helms was a very talented fellow who had a few other hits. "My Special Angel" was a biggie for him, but I can remember only a bad white-boys-in-sweaters cover of that one by the Lettermen or the Vogues in the late '60s. Garland went on to be quite a jazz guitar player after he left Nashville behind, but when last heard from he was still pretty bitter about not having the royalties from "Jingle Bell Rock" to live off in retirement. Helms died about five years ago, and from what I could read, he laughed the whole thing off. Hank, Bobby, wherever you are: You should have seen the look in my kid's eyes tonight when that song came on the second time. There isn't enough money on earth to pay you fairly for that. |

|